A Conversation with the Founders of New England Center for Circus Arts

They came. They soared. We were conquered. Elsie Smith and Serenity Smith Forchion brought the circus to town, forever changing thousands of lives.

By Jerry Goldberg/

I first became aware of the Smith sisters when they brought their circus-production company, Nimble Arts, to the scene. Whether they knew it at the time, their blend of artistry and athleticism was to be, as the old song goes, “the start of something big.”

Something called the New England Center for Circus Arts.

It’s as though the eager child in all of us had been waiting too long for the circus to come to town, and it has come at last. NECCA brings with it the forever truth that we, too, can learn to fly.

I wended my way through the mysterious, magical halls of the Cotton Mill’s third floor to the NECCA offices and, for an hour, was reminded of how lucky we are to have Elsie Smith and Serenity Smith Forchion on our stage.

* * *

Jerry Goldberg: So take us backstage. How did all this begin?

Elsie Smith: Our mom and dad were homesteaders struggling to make it on a piece of land in Huntington, Mass., a small town not far from Springfield. We lived in a little log cabin with no running water or electricity. Believe me, the grid was nowhere in sight.

As our brothers and sisters came along, our parents got to be increasingly more mainstream. Dad, who’d been a journeyman logger, became a sawmill owner and then a forester. And mom, who’d been a midwife, went to medical school.

Serenity and I were academic kids who climbed trees with our books in tow. We got pretty good at balancing both, which kind of explains where we were with our physicality.

As our high school years were ending, it was clear that the only way college could happen was to stay in state and pick up scholarships. The University of Massachusetts, Amherst delivered both.

Serenity Smith Forchion: In 1988, while we were in the first of our two years at UMass, our mom was invited to a conference at Club Med and took us along. There was a flying trapeze on the premises. We got right to it — and once we learned to “fly,” we were hooked.

Back then, there was nowhere in this country where you could learn — or learn to teach — circus. You’d have to go to Europe for that, so for us apprenticeship would be the way.

We found a summer camp in upstate New York called the French Woods Festival of the Performing Arts that had a program run by Circus of the Kids. We apprenticed there in 1989 and 1990. The connections we made paved the road for us, so when the apprenticeship ended, we were off and running and didn’t come back — except for a few six-month stints — for about 11 years.

J.G.: Take us on that road with you.

E.S.: I stayed with the Circus of the Kids and toured the East Coast for two years. That was from ’89 to ’91. I then went to Ontario to train to be a trampoline instructor. I got my coaching certification and did trampoline for three years, from 1992 to ’94.

S.S.F.: In summer ’89, I signed on with Ringling Brothers and also worked in Japan with another circus troupe until 1990. From there I went to San Francisco to teach, which I did from 1991 to ’97. Elsie joined me there in 1995.

The Cirque du Soleil signed us both on in 1998, and we performed with them until the end of our contract. That was 2001.

J.G.: So how’d you find your way to southeastern Vermont — not exactly the center of all things circus, right?

E.S.: Our dad, Steve Smith, had purchased an old run-down farm in Guilford through the Vermont Land Trust and moved the family up. Serenity and I used it as our tax address throughout the time we were away.

Dad kept us in on the goings-on at the Hooker-Dunham Theater — I guess his way of saying, “See, Brattleboro is a really cool town. You ought to think about living here.”

When we finished up with Cirque and decided that it was time to land somewhere, we looked for a place that we could travel to and from easily.

S.S.F.: Although I was starting a family — I have three children today — Elsie and I had every intention to continue to travel the world and to teach and perform. A handy Amtrak and proximity to the Hartford airport helped us choose Brattleboro to be our home base.

J.G.: What about “here” appealed to you?

E.S.: We’d grown up country girls and left town to perform in the biggest cities in the world. Brattleboro was able to give us access to the metropolitan requirements of a performing career as well as the ability to live off the land again.

S.S.F.: There’s a sense of place about Brattleboro. It has a “big-city” cosmopolitanism and hip kind of culture. Incidentally, that’s ended up being amazingly beneficial to our business, because people come here to study or work and they experience that sense of place. They feel that Brattleboro is itself every bit as enticing as NECCA.

J.G.: Let’s go back to that “live off the land” comment.

S.S.F.: After all that time on the road, the idea was to create a home. My husband Bill Forchion and I purchased a hidden gem of a property off Meadowbrook Road in West Brattleboro. Bill’s an artist who works in many disciplines, including acting, dancing, filmmaking — and even circus performing.

E.S.: My husband Jim Westbrook and I built an off-the-grid almost-tiny-house cabin on a portion of Serenity and Bill’s land that became Jim’s Cherry Hill Farm — a pig and mushroom operation. Best pork sausages around!

J.G.: That qualifies as “land,” all right! And home. How did you hook into what was going on here?

S.S.F.: When we first arrived, the performance community couldn’t have been more welcoming. Stephen Stearns, co-founder of the New England Youth Theatre, brought us into his vision of the Downtown Arts Campus—

E.S.: —and Eric Bass of the Sandglass Theater up in Putney was also great to us. I guess they both saw the potential that circus would have for kids.

J.G.: OK, but here you are with a school. How did that come about?

S.S.F.: We certainly didn’t set out to start a circus school. But shortly after we got here, people said, “Oh, you teach trapeze? Can you teach my kid? Heck, can you teach me?” So we took space here at the Cotton Mill with the sort of casual, “We’ll teach when we’re in town” attitude, knowing that most of our work would be performing out of town.

Then Kurt Isaacson, who was running the Brattleboro Development Credit Corporation at the time, approached us about entering the BDCC’s first-ever Business Plan Competition.

E.S.: I remember saying to him, “We’re performers who also teach. We’re not into building a business. OK, we might end up with two or three people working for us, but that’s not our focus.”

Kurt urged us to apply anyway, which we did. Our plan was for a circus school — and it won us the competition.

S.S.F.: The “seal of approval” that came with it enabled us to step out into the local community and the broader Vermont community not solely as circus artists but as business people.

E.S.: We were invited to consult at various local and state business forums and to meetings with the governor and other state officials. The BDCC really helped give us that kind of exposure.

J.G.: Tell me more about how the state supported you.

S.S.F.: The Vermont Arts Council helped us secure a three-year grant to help us grow our offices. We were also awarded considerable funding from the state to use in the development of our new building complex up on Putney Road.

E.S.: One of the programs that helped us — and continues to — is the Vermont Student Assistance Corporation. NECCA is in an interesting position because we’re not an accredited institution. We’re essentially a trade school for higher ed — and traditional student-assistance paths aren’t open to our people. VSAC is where our students can get loans to study the circus trade, which is phenomenal. Vermont might be the only state with such a unique program.

S.S.F.: Small states can get things done for small start-up businesses like ours. It’s easier to connect. It’s easier to find the right ears to talk to.

J.G.: What about obstacles? Stuff happens.

S.S.F.: Even with the state’s assistance, by far the biggest challenge facing us and arts organizations in general is funding. That’s especially so for anything “circus.”

As a not-for-profit, we’ve benefited from economic grants and support from the community in economic development work. As to the circus aspect, it’s been very difficult to secure loans and identify grants because circus doesn’t easily fit into a pocket.

Listen: only recently, after many years of petitioning, has the National Endowment for the Arts agreed to recognize circus as an art form — one fundable like other theater programs.

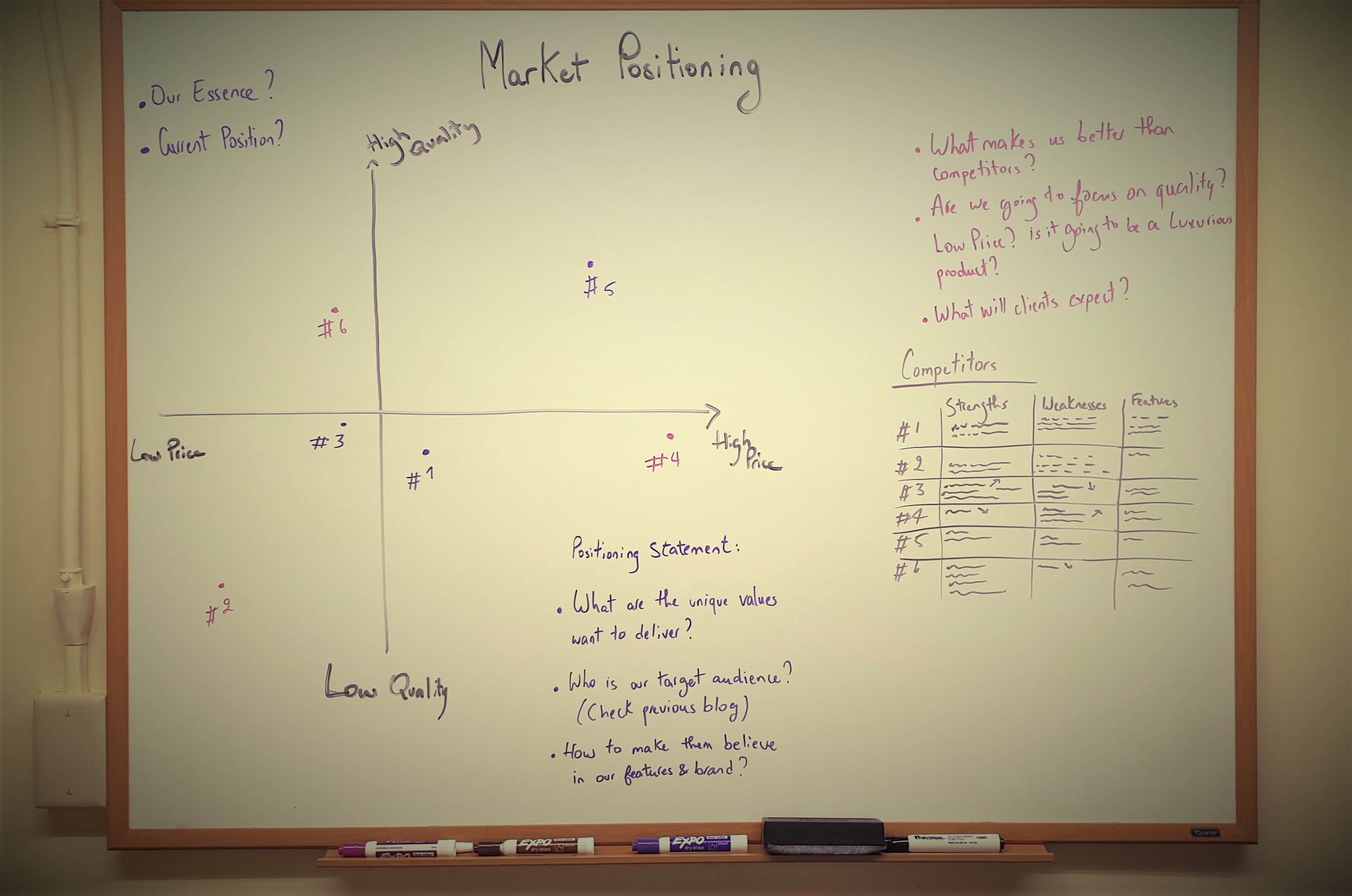

J.G.: I’m sure you’ve had to work at marketing circus to that investing audience, making it a palatable and attractive venture for them, if you will —

E.S.: — and educating the general public that NECCA’s not just an odd little group of circus people teaching and performing cool things. Circus is a national and international art form that has been well-respected for hundreds of years, especially in Europe and Asia.

J.G.: Real quick: You came here in 2002 and Nimble Arts was your entity as a performance brand. When did Nimble Arts officially morph into NECCA?

E.S. and S.S.F.: 2007. [Yes, that was said in unison. Remember, they’re identical twins! —J.G.]

J.G.: You’ve been working together here in town for almost 10 years, nine at NECCA. Who does what?

S.S.F.: Elsie manages the adult performance programs and the overall scheduling of activities at the school. I oversee youth performance and all the special events.

We both teach as much as we can squeeze in — mostly aerials and injury prevention/rehabilitation/occupational therapy work.

J.G.: How many staff do you have?

S.S.F.: In the summer when we’re running camps and a lot of outreach programs, we write paychecks to about 50 people. During the rest of the year, it’s about 30.

J.G.: Wow! I had no idea.

Circus requires specialized skills. How do you find folks who have ’em?

S.S.F.: There are two basic ways.

One, they come to us. They may take classes and then move on to our teacher trainings — a big part of what we do. Then we see if we can find a connection with them, or we look at what we need and see if they fit.

The second way is us going to where they are. Because we do a lot of teaching nationally and internationally, we end up meeting a lot of highly qualified, high-potential people.

E.S.: We’re seeking people who are of a certain age, who as performers or artists are looking to settle down but can’t afford to in some of the bigger cities — much the same as us.

Sure, San Francisco, Montréal, and New York are circus capitals, but none of us could afford a house there — not to mention a house for kids and a dog.

J.G.: Or all the family accommodation stuff.

E.S.: Exactly. We push that as a benefit if someone wants to have a full-time circus-teaching career. They can have a normal lifestyle here in Vermont. Where a different business wouldn’t be able to sell that as a plus, we can because we’re not competing with a circus school in another affordable town down the pike. We have a unique franchise around here.

J.G.: When you launched NECCA, you were business novices. Did you make any mistakes or do anything that taught you hard-learned lessons?

S.S.F.: Here’s something that’s not necessarily a mistake, but is more of a lesson in adapting to a shift in the way business is done.

I’d heard a public service announcement on the radio about employers needing to categorize their workers as either regular employees or as independent contractors. Apparently, this has been a political hot potato for some time.

When we first started, we worked with the BDCC and the Small Business Administration to help us stay on the right side of that question. Every year since, we’ve checked back with them to make sure we’re still good.

E.S.: About three or four years ago, we started purchasing worker’s compensation for everyone — regular employees or not. Although that put us in a difficult spot fiscally, I don’t think it was a mistake. Ours is a physical business, and we wanted to be fair.

That has changed in the last year or so. Now, pretty much everyone who works for us is treated as an employee. Sure, it challenges the budget — but it’s clear. We know what we have to do. It’s the cost of being in business.

J.G.: What about health insurance?

S.S.F.: We’re working on that. Our last few hires asked about it immediately in the interviews. With the shifting of the Affordable Care Act and how our state participates, we want to get it right — for us. There’s a lot to grasp, so we’ve just recently passed it to our board of directors to look into. We’ll get there!

J.G.: How many students do you have? And how many people in the aggregate experience NECCA during the course of a year?

E.S.: Last year, we had 2,000 students and maybe 6,000 in all who participated in circus. A lot of people just come to our shows. So it’s quite a few. We also teach a lot of programs outside the region. If you add the people Serenity and her colleagues teach in Ireland, it adds up.

J.G.: So, circus people, it looks to me like you’re wearing the mantle “entrepreneur” well. Talk to me about how that is for you.

E.S.: It’s interesting, because even though we didn’t set out to be entrepreneurs, we became what I call “sort of” entrepreneurs, because unlike a classic entrepreneur we don’t actually own our business. NECCA’s a not-for-profit public entity with a board of directors. Yet Serenity and I have the mindset and quality of dedication similar to owners of their own businesses.

S.S.F.: The difference is that we don’t reap all the benefits of ownership. That’s where the “founder’s syndrome” comes in for many not-for-profits.

J.G.: Founder’s syndrome?

S.S.F.: Most not-for-profits — especially arts and education organizations — are the product of the inspiration and hard work of their founders — those who had the vision — and also of the amazing generosity of their boards of directors or trustees.

That can carry an organization for years. Yet later, when a founder ages out or retires, there’s the issue of replacing his or her contribution.

How do you buy that absolute dedication? You can’t just pay someone for it.

E.S.: I’ve worked with several other arts organizations around town to look at pay equity. In all but one of the organizations I interviewed, the lead — the person the community would identify directly as “head” of that organization — is grossly underpaid for the amount of work they do.

These leaders admit it freely, yet they wouldn’t change it because of the passion they have for their organization and the causes they serve.

This means that many passion-driven, founder-based arts entities have to go through some stringent re-budgeting to get past being founder-driven. So far I haven’t seen them doing that very effectively.

It’s only been a couple of years since I started looking at this, but that’s one of the things we’re all trying to be careful of — accurate budgeting for when the founders are no longer active.

E.S.: This is really important to us right now because we’re in the middle of a build project that will carry NECCA hundreds of years into the future. So we can’t afford to look just 10 or 20 years ahead. We have to look 50 years out and make sure we’re considering all of that — and budgeting for it.

J.G.: As you’ve gone about raising money for the land and the new buildings on Putney Road, you’ve been on the stump a lot. Is there anything to add to making the case?

S.S.F.: It’s important for us to communicate that we’re a smart business, that we run in the black, and that we’re strong — while at the same time letting people know that we still need support from granting organizations and from the community for all the outreach we do and the scholarships we provide.

There’s that dichotomy in how we are perceived.

E.S.: We’ve become passionate about the idea of creating a destination, not just a facility. I’d like people to know that we’re building a venue, a site for circus, that we hope will be to circus what Jacob’s Pillow is to dance and Tanglewood is to music — a place for art and education and youth and adults and regional and national and international and indoor and outdoor and festivals and private lessons and the scope of that 3{1/2} acres just north of downtown Brattleboro.

J.G.: Jacob’s Pillow. Tanglewood. That’s quite a vision. I applaud you for having it.

S.S.F.: Thank you. We actually were guest performers at Jacob’s Pillow last year. It was a beautiful experience.

J.G.: The whole Berkshires area’s got it going on. What we would like to have here. What we can have here — with people like you who dream big.

So, it’s time to tell a story. Every organization, every company — for- and not-for-profit — has one, you know. A story.

What do you think people think the NECCA story is? And are you sure that’s the right story?

E.S.: We’d like it to be that we’re a broad organization that does a lot of things.

It’s been hard for us to come up with that “elevator speech,” where we tell people that we do social circus, that we help kids with their self-esteem, that we do physical training for people just to get them fit, that we create art, and that we work with performance professionals who are going all over the world to train. We also do occupational therapy for people who are either missing limbs or don’t have full use of the limbs they have.

Believe it or not, I’m even probably forgetting a couple of the categories.

S.S.F.: So it’s really difficult, for example, for someone who sees a snapshot of cute kids doing amazing circus things on Main Street during Gallery Walk to get the full picture. Or for someone else who sees our high school programs or our Circus Spectacular — again, all snapshots — to get that full picture.

J.G.: Is there anything coming up that you’d like folks to know about?

S.S.F.: Yes! On Thursday, Sept. 29, we’re breaking ground on phase one of the Putney Road project. We’re so excited about that. We’re also excited about being about halfway through fundraising for the second phase as well.

E.S.: Our Flying Trapeze recital follows on Sunday, Oct. 2 on the new property, which will be a great way for people to see where we’re building — and why.

S.S.F.: There’s the Open Studio weekend here at the Cotton Mill on Dec. 2–4. We put on a free recital as part of that, and we offer sample classes.

E.S.: And finally, The Flying Nut is the next big performance in our professional programs. It’s a reinterpretation of The Nutcracker that we put on right before Christmas every year.

J.G.: Seen it. Loved it. I’m a Nutcracker groupie!

OK, play me off. Circus is about thrill. What about it and about NECCA thrills you?

E.S.: I love the community of circus — wandering the halls, peeking into the studios, and seeing people helping one another, challenging one another, admiring successes, and sharing struggles.

I like accomplishing projects — getting all the ducks in a row and finishing something. There’s something thrilling about us growing as a business. I never dreamed I’d say that!

S.S.F.: I love the diversity of circus — how adaptable and inclusive it is. Seeing how students and audience members are engaged makes me so happy.

I am also honored to be part of the teaching of physical literacy — having the motivation, confidence, physical competence, knowledge, and understanding to value and take responsibility for engagement in physical activities for life.

J.G.: For life. L’chaim! And thank you both.